NBA Stats

NBA Estimated Impact A player rating that uses elements from the box score only.

- 1952-2015 Estimated Impact

- 1952-2014 Playoffs Estimated Impact

- Career Estimated Impact

- Weights for box score elements were found via regression onto rapm. Estimated Impact has much more predictive value than other popular box score metrics such as PER or Win Shares.

NBA Non Prior Informed RAPM (“NPI RAPM”) A player rating that is based on team point margins in stints where the player was on the floor. This is the most basic version of RAPM and only uses data from the year in question.

NBA Prior Informed RAPM (“PI RAPM”) A version of RAPM that uses information from previous seasons to increase stability and predictive accuracy.

NBA Boxscore Informed RAPM (“BI RAPM”) A version of RAPM that uses information from the box score to increase stability and predictive accuracy. In this version, RAPM is calculated with estimated impact, rather than 0, as the prior, then mean regressed somewhat.

Pace and Ratings (1952-2013) An estimation of each team’s possessions and the rates at which they use those possessions.

NBA Average Height by Position and Year (1952-2014)

Estimated Impact

While I initially introduced my player rating, Estimated Impact, a while ago, I recently gave it a pretty extensive makeover and I’m generally pleased with results. My goal was basically to create a box score only metric that is a) more accurate and better at predicting future team performance than other box score metrics, and b) a very reasonable snapshot of present and historical player performance. Obviously, box-score only metrics have their noted limitations. And maybe more obviously, all-in one metrics are merely a two-dimensional picture of a three-dimensional world. But I’m confident that Estimated Impact does a good job at accomplishing my goals.

I don’t want to bore you with the details so I’ll keep it basic. This metric is based on a regression of certain box score elements against long term RAPM. For each season, I fit each player’s result to the team’s efficiency differential (this is usually a pretty small adjustment). I did the same with offense only and defense only, then fit off + def to total impact. For 1974-1977 I estimated turnovers by regression and used the same formula as I used in post-77 seasons. For pre-1974, I ran new regressions without any use of steals, blocks, etc. Needless to say, pre-74 estimates are probably less accurate. They’re certainly far from useless though, and they’re probably superior to any other measure of pre-74 production (e.g., WS/48 or PER).

In my own retrodiction testing, Estimated Impact outperforms every box score metric that I know of, and performs nearly as well as 2000s xRAPM [edit: when adjusted to give a fixed rating to very low mp players, estimated impact significantly outperforms xRAPM in retrodiction testing as well] (I’d welcome anyone to reproduce my results). And so I’m confident that it is currently the best all-in-one metric with respect to estimating historical production. For what it’s worth, the results also seem very reasonable to me. You can see all results from 1952-2013 here, or at the NBA & NCAA Stats page at the top right of the site. Or you can download the database here. Enjoy!

-James

NBA & NCAA Stats Page

I added a new page called NBA & NCAA Stats (you can see it up in the top right corner). I’m basically using it to keep all the stats that I think are interesting or helpful but either can’t be found anywhere else or are really hard to find. You’ll notice I have RAPM from 2001-2013. I want to make it clear that this is not my RAPM, but was previously published and isn’t really publicly available anymore. I also added historical pace, which includes offensive rating, defensive rating, relative offense, relative defense, and efficiency differential for every team since 1952. I posted on this a few months ago, but I think it will be more useful to keep it in a more easily accessible place. Finally, I added Estimated Impact, my box score metric, which will get its own post soon. If there is anything else anyone would like to see (for example, I was thinking of doing a spreadsheet with substantially all available player metrics for each player), let me know and I’ll see what I can do. Anyway, enjoy!

-James

Draft Model Update

I have made significant changes to the draft model; it’s very refined at this point and much improved from the previous iteration. To avoid confusion, I’m going to make this the go-to post and take down all posts pertaining to the earlier versions. But I’m going to use a few quotes from them so they’re not lost.

From my post called “NBA Draft Projection Model and More”:

I’ve been working on developing a model that attempts to project NBA performance of college players. Basically I ran multiple linear regressions on pretty much all the data I could collect (like pace-adjusted box score numbers, team sos, measurements, etc.) for college players from 2002-2009 against their career NBA RAPM. I removed insignificant factors, and eventually came up with a fairly reasonable predictor.

From my post called “Draft Rankings!!”:

I’m obsessive by nature, so this certainly won’t be the final iteration, but I’m pretty happy with it at this point…

…The results are far from perfect as they probably always will be – remember what we’re doing here, we’re taking stats from college kids playing against varying levels of competition in a very limited sample size and trying to project their careers. But I feel pretty confident that we can make educated guesses with this data – and do a much better job than what we’ve actually seen in the past.

I made a number of changes, but the following is a brief summary of the most significant ones:

- I added in all players’ career numbers instead of using only their numbers from their final NCAA season. This turned out to be a very significant improvement, and I probably should have done it in the first place.

- I went back to using ONE regression rather than three different ones (for points, wings, and bigs – an idea I had taken from Hollinger). I was able to do this because of having the career numbers. This is important because all players can be more reasonably compared to each other regardless of position, and now everyone is on a sliding scale – for example, the difference between someone who plays a bit more SF than PF and someone who plays a bit more PF than SF is very small now, which is the way it should be.

- I refined and normalized the y values (the dependent variable for each player). Instead of using long-term RAPM, I used a RAPM-SPM blend based on the same relative period of time for each player.

Here are some observations about what player projections mean:

- Like before, players +2 or better are very likely to be all-star caliber NBA players. The +2 club is more exclusive than before, and so if there’s a +2 on the board when your team is picking, take him.

- +1 or better means the player is very likely to be a solid NBA player. In some cases – usually if the player has behavioral or work ethic issues – +1s won’t pan out, but more often than not, they will.

- Players in the positive or slightly negative range are more likely than not to be solid contributors.

- Players more than slightly negative will be hit and miss. You probably won’t find may great players here, and the more negative, the less likely it is the player will be any good.

Finally, here are all the out-of-sample (2010 to 2012) results for drafted players:

And as always, the current draft rankings can be found at the top bar.

-James

It’s a Good Year to Move Up in the Draft

Generally speaking, I would discourage any team from trading its assets to acquire a higher draft pick. This is because, frankly, there just isn’t a lot of value in most drafts. Only a handful of good players will come out of any given draft, including about five all-stars per year. And teams generally perceive their high picks (especially when we’re talking top five) to be more valuable than they really are. In fact, the only pick that more often than not turns out to be a high impact player is #1. So trading up is usually a bad idea unless it either allows you to get a large, unwanted contract off your hands or you trade up a spot or two and it doesn’t cost you much.

But this year is a bit peculiar. It is almost universally considered to be a “weak” draft, especially after the decisions of a number of high profile potential draftees (Marcus Smart in particular). More specifically though, it’s viewed as a draft with a handful of solid players but no sure-bet all-star types. Accordingly, a pick in the two to five range isn’t viewed as that much better than a pick in the six to fourteen range this year, at least if you believe the prominent media, who purportedly have a great deal of contact with the general managers who actually make the decisions.

And that’s exactly where you can pull a fast one this year. In the three to eight range sits a man named Otto Porter. Now, I’m not Miss Cleo or John Titor, but my draft model has Otto as better than a +3. And if you recall, I consider +2 or better to be as close to a sure thing as you’ll see.

In other words, I believe Otto Porter has a pretty good chance to be an all-star caliber NBA forward a few years down the road. Don’t let Georgetown’s poor performance in the tournament fool you, Otto’s supporting cast was not particularly impressive, and the fact that they rode his coattails to the Big East’s best record is remarkable in itself. I think it’s actually a testament to Otto’s ability to lift an average team to elite levels. And that shouldn’t be a surprise if you watched him play this year. He is a do-everything type player who puts up superb numbers across the board and adds plenty of intangibles that don’t show up in the box score. He is a very good shooter (and scorer) in spite of his shooting form. He’s also an excellent if underrated passer who has a LeBron-esque ability to find the open man anywhere on the court. And while he lacks elite athleticism, he makes up for it with craftyness, a high basketball IQ, and a great overall feel for the game. He is also valuable because of his ability to play either forward position on both offense and defense and have a matchup advantage against most of the league because of his size-skill combination. This is a 6-8 guy with a 7-2 wingspan who shot 42% from long range and showed a terrific ability to steal the ball, block shots, and simply menace opponents on defense. Because of all this, I think that he’s arguably the best player in this class.

And that’s why I think it’s worth taking a shot to try to move up to a position where you can draft Porter. Of course this is easier said than done, but if your team has assets of some value, it’s worth making some calls to see what you might be able to get for them, especially if the assets are either expiring contracts or reasonably expendable given their relative value or redundancy. Because of the overall lukewarm attitude toward this draft, I’m willing to bet that someone will listen. And if you can spin this kind of asset into Otto Porter, I’m confident it will have been well worth it.

Pre-1974 Pace And More

Before 1974 they didn’t track turnovers or offensive rebounds for NBA teams. Because of this, we are missing pieces necessary to estimate pace, which can be super helpful in understanding team strengths and even player contributions. However, it’s possible to get a reasonable estimate of pace by using regression analysis and making reasonable inferences. I was particularly intrigued by the methods employed by ElGee, who posted his results a year or so ago. Unfortunately, something went wrong with his site, and none of his data is available anymore. Luckily, Opposing Views reblogged his post, and I was able to find his formula, which is as follows:

Pre-1974 Pace = (FGA + 0.4 * FTA – ORB% * (FGA – FG) + (-TOV% * (FGA + 0.44 * FTA) / (TOV% – 1))/G), where ORB% = 0.319 for1971-1973 and 0.303 for before 1971, and TOV% = 0.158 for 1971-1973 and 0.161 for before 1971.

Using this information, I figured I’d post the estimated pace for all teams from 1951-1973 (before 1951 we don’t have rebounds, so there’s no way we’re gonna be able to estimate further back than that). Additionally, with pace (possessions per game by the way, though I’ll probably add possessions per 48 soon), I can calculate Offensive Rating and Defensive Rating – points scored per 100 possessions and points surrendered per 100 possessions, respectively. And with Offensive and Defensive Ratings I can estimate Relative Offense (Ortg – League Avg Ortg), Relative Defense (League Avg Drtg – Drtg), and Efficiency Differential (Ortg – Drtg). So I made a spreadsheet and included all this stuff for anyone interested in finding all these numbers, including the post-1973 estimates, in one place.

For fun, here are some top tens:

Top Ten Efficiency Differentials:

- 1996 Bulls, +13.4

- 1997 Bulls, +12.0

- 2008 Celtics, +11.3

- 1992 Bulls, +11.0

- 1971 Bucks, +10.9

- 1972 Lakers, +10.5

- 1972 Bucks, +10.1

- 2009 Cavs, +10.0

- 1994 Sonics, +9.6

- 1997 Jazz, +9.6

Top Ten Relative Offenses:

- 2004 Mavs, +9.2

- 2005 Suns, +8.4

- 1971 Bucks, +7.8

- 1997 Bulls, +7.7

- 2010 Suns, +7.7

- 2002 Mavs, +7.7

- 1998 Jazz, +7.6

- 1996 Bulls, +7.5

- 2007 Suns, +7.5

- 1982 Nuggets, +7.4

Top Ten Relative Defenses:

- 1964 Celtics, +10.9

- 1965 Celtics, +9.5

- 2004 Spurs, +8.8

- 1963 Celtics, +8.6

- 2008 Celtics, +8.6

- 1962 Celtics, +8.5

- 1993 Knicks, +8.3

- 1973 Celtics, +8.2

- 1994 Knicks, +8.0

- 1961 Celtics, +7.7

Again, the pre-1973 estimates aren’t as accurate as their modern counterparts, but they come reasonably close, and that’s what we’re going for. What I find particularly interesting is the number of Nash offenses and Russell defenses in their respective top tens (5 each).

-James

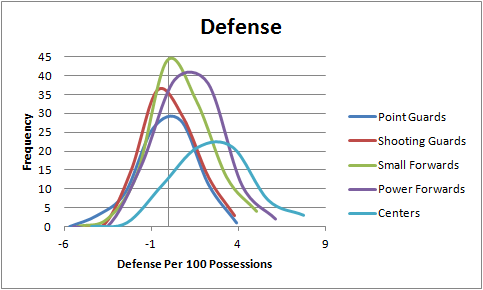

The Importance of Position on Offense and Defense

Perimeter players aren’t as important on defense as bigs. And bigs aren’t as important on offense as perimeter players. I’ve heard this assertion made quite a few times. I’ve even made it myself. But is it true? When I wrote the post arguing that Trey Burke should be an early lottery pick rather than a mid-first-round pick , I noted that Burke’s “troubles” on defense are not particularly concerning because he is a point guard, not a big. This got me to thinking: sure, certain bigs have way more impact on defense than any perimeter player could ever hope to, but does that mean bigs are more “important” on defense? Instead, isn’t the difference between a good big on defense and a bad big on defense the same as the difference between a good guard and a bad guard? The best defensive guards have much less of an impact than the best defensive bigs, but aren’t the worst defensive guards as substantially worse than the worst defensive bigs? On the other hand, isn’t the discrepancy between Garnett and Bargnani (or Larry Sanders and David Lee, if you’re a Goldsberry fan) a lot bigger than the discrepancy between say, Rajon Rondo and Steve Nash? Then again, maybe it isn’t. I decided to investigate.

In order to answer my questions, I looked at J.E.’s 12 year RAPM data, which includes every player’s regularized APM from 2001 to 2012. I excluded players who played less than 20,000 possessions because their RAPM values are much more uncertain. I separated all players by position with an assist from basketball-reference. Then I looked at the offensive and defensive ranges for each position.

I found the following:

On defense,

- ~95% of point guards fall between -4.1 and 2.3 per 100 possessions (a range of 6.4)

- ~95% of shooting guards fall between -3.6 and 2.3 (a range of 6.0)

- ~95% of small forwards fall between -3.5 and 3.3 (a range of 6.8)

- ~95% of power forwards fall between -3.5 and 4.2 (a range of 7.7)

- ~95% of centers fall between -2.4 and 5.7 (a range of 8.1)

- While there is a bit of a difference across positions – i.e., centers may be a bit more important than guards – the difference is not statistically significant (e.g., the hypothesis that each position will have the same range is accepted). This is true even if we include the entire range for each position and not just two standard deviations from the mean.

On offense,

- ~95% of point guards fall between -3.4 and 4.2 per 100 possessions (a range of 7.5)

- ~95% of shooting guards fall between -3.8 and 4.3 (a range of 8.1)

- ~95% of small forwards fall between -3.8 and 3.8 (a range of 7.6)

- ~95% of power forwards fall between -4.2 and 2.7 (a range of 6.9)

- ~95% of centers fall between -5.2 and 2.6 (a range of 7.8)

- Again, the variance on offense among positions is not statistically significant.

Here are a couple of graphs for those who like visualizing data:

So, basically, as we expected, the big guys are better on average on defense and worse on average on offense. But when we look at their ranges, their relative importance is pretty much the same. Now, of course, more work needs to be done here. 12 year RAPM is likely a good overall indicator, but it’s certainly not the ultimate source for everything (nothing is). It would be interesting to see a study like this replicated using other data, whatever it may be. But, for now at least, it doesn’t appear that certain positions are significantly more “important” than others on either side of the ball, though they can certainly be more impactful. Starting a little guy at center, for example, is obviously a bad idea. But the difference between a bad center and a good center doesn’t seem to be significantly different from the difference between a bad guard and a good guard.

-James

Some Past Results

I’ve had a lot of people asking me about previous years, etc. of my draft model, so I thought I’d post a couple of things. Here’s the top twenty prospects from last year and the top ten at each position overall. Remember that only 2010, 2011, and 2012 are out of sample. Also, please keep in mind that this model is ever-evolving and these numbers are subject to change in the future, especially as more data becomes available.

Top 20 from 2012:

Only Davis, MKG, and Drummond were better than +1, and only Davis was better than +2.

1. Anthony Davis

2. Michael Kidd-Gilchrist

3. Andre Drummond

4. Jared Sullinger

5. Bradley Beal

6. Dion Waiters

7. Maurice Harkless

8. Damian Lillard

9. Terrence Jones

10. Harrison Barnes

11. Tyler Zeller

12. Meyers Leonard

13. Quincy Miller

14. Jae Crowder

15. Royce White

16. Kendall Marshall

17. Thomas Robinson

18. Jeremy Lamb

19. Draymond Green

20. John Henson

And here are the top tens by position:

| Top Ten Point Guards | Year | Projected Impact |

| Kyrie Irving | 2011 | 4.9 |

| Chris Paul | 2005 | 3.5 |

| Derrick Rose | 2008 | 3.2 |

| Jrue Holiday | 2009 | 3.0 |

| Russell Westbrook | 2008 | 2.8 |

| Mike Conley | 2007 | 2.7 |

| Stephen Curry | 2009 | 2.0 |

| Kyle Lowry | 2006 | 1.9 |

| John Wall | 2010 | 1.8 |

| Raymond Felton | 2005 | 1.8 |

| Top Ten Wings | Year | Projected Impact |

| Kevin Durant | 2007 | 5.6 |

| Carmelo Anthony | 2003 | 2.9 |

| Marvin Williams | 2005 | 2.7 |

| Luol Deng | 2004 | 2.7 |

| James Harden | 2009 | 2.4 |

| Dwyane Wade | 2003 | 2.3 |

| Tyreke Evans | 2009 | 2.2 |

| Danny Granger | 2005 | 2.1 |

| Xavier Henry | 2010 | 2.0 |

| Rudy Gay | 2006 | 1.8 |

| Top Ten Bigs | Year | Projected Impact |

| Anthony Davis | 2012 | 3.4 |

| Kevin Love | 2008 | 3.2 |

| Greg Oden | 2007 | 3.0 |

| DeMarcus Cousins | 2010 | 2.7 |

| Blake Griffin | 2009 | 2.5 |

| Andrew Bogut | 2005 | 2.4 |

| Chris Bosh | 2003 | 1.9 |

| Hasheem Thabeet | 2009 | 1.8 |

| Michael Beasley | 2008 | 1.8 |

| Derrick Williams | 2011 | 1.6 |

Otto Porter looks like the second best wing prospect in the last ten years. And Marcus Smart, Nerlens Noel, and Trey Burke each make the top ten for their position. It’ll be very interesting to see how these guys pan out.

-James

Shabazz Muhammad: The Second Coming …of O.J. Mayo

The NCAA stirred controversy earlier this season when it initially ruled Shabazz Muhammad, the best prospect in the nation, ineligible due to slave amateurism violations. This all added to the Shabazz hype – at the time, he sat alone atop most mock drafts for 2013. O.J. Mayo, too, was a hype machine – one of those rare household names before he was even in college (at least, if your household is full of huge basketball fans). I found the first minute of this video particularly amusing : “is this guy as good a prospect as LeBron James?” “Yes.” But despite being (allegedly) illegally paid to go to prominent Los Angeles schools, neither O.J. nor Shabazz seemed to live up to the hype in college, especially when you venture beyond their scoring totals.

With a quick glance at the box scores, you might think Shabazz is everything he was supposed to be: he’s averaging over 18-per-game and his team finished the regular season on top of the Pac-12 standings. Just the other week, in fact, the beat writer for my beloved Washington State Cougars observed the following:

Students chant “overrated” at Shabazz Muhammad, which is an odd thing to chant at the conference’s second-leading scorer.

— Christian Caple (@ChristianCaple) March 7, 2013

But when you look past the scoring, it becomes apparent that Shabazz is essentially one-dimensional. Specifically, of the wing players who have a shot at being drafted this year, Shabazz falls in the bottom 20% in steals, and the bottom 10% in defensive rebounds, assists, and blocks.

Ignoring the other numbers for now, Shabazz’s assist numbers are particularly alarming. We can sit and argue the value of the subjective assist stat all day, but I’m confident we can all agree that it has value. And it becomes especially important for guys, like Shabazz, who use a lot of possessions because good scorers will get double teamed in the NBA, and when they do, they need to be able to find the open man. Shabazz’s assist rate is 5.8%. That means less than six percent of his teammates’ field goals are assisted by him when he’s on the floor. That’s astronomically low, especially for someone who is supposed to be a great offensive player. To illustrate this point, here is a list of all guards who have had at least ten win shares in an NBA season while maintaining an assist rate of six or less. (there’s not an error, there are zero guys on the list.) Ha! Ok, let’s give some leeway: here’s the same list, but with the minimum assist rate moved to ten.

The list is nine seasons long. Three of them belong to Peja Stojakovic, who was basically an elite role player – one of the best spot up three shooters the league has ever seen. One belongs to Dale Ellis, who was probably a bit more offensively versatile than Peja, but was still primarily a spot up shooter. Both were good scorers, but were always surrounded by other good offensive players – Peja had C-Webb and was on Kings teams where everyone was basically a scoring threat; Ellis had Xavier McDaniel and Tom Chambers. In contrast, Shabazz Muhammad is supposed to be a primary offensive threat – someone who you can give the ball to and let him go to work. Plus, while he’s a good shooter, he’s not near the level of Peja or Ellis, and would likely have trouble filling roles like theirs in an offense.

Two of the nine seasons on the list belong to Chet Walker and one belongs to Doug Collins. These guys played (at least with respect to the seasons in question) before we measured steals, blocks, or turnovers; the “10” win shares are much more an estimation than they are for the other players on the list. Then we have Marques Johnson and Adrian Dantley. Whether or not these guys actually even played “guard,” their style of play is not even remotely similar to how we see guards play today. And so it’s difficult if not impossible to compare Shabazz to any of these guys. As a result, it’s apparent that Shabazz’s current inability to assist baskets ain’t gonna fly in the big league. It almost necessarily puts him in a role-player box, which is fine, but isn’t what you want from a super-high draft pick. And it’s certainly not what you want to see from your primary option on offense, especially with today’s sophisticated defenses that will undoubtedly force Muhammad to make tough passes in certain situations.

Ok, now let’s talk about Muhammad’s D. While defensive numbers are just a small part of measuring a player’s defensive contributions, they nevertheless matter. I have already noted that, out of the wings drafted in the last ten years that stole the ball at 1.5 times per pace-adjusted 40 minutes or less, none have been all-stars. Shabazz is below 1.0. Things begin to look even worse when we look at his poor shot blocking numbers. Sure, shot blocking isn’t particularly important when we’re evaluating shooting guard/small forward types, but it can be indicative of defensive effort and ability. And just like steals, history is not very kind to wings who can’t block shots in college. Specifically, if we look at wings who blocked 0.4 or less shots per pace adjusted 40 from 2002 to 2012 (Shabazz blocked less than 0.2), none have been all-stars, and the best of the bunch have only been marginally successful (Rodney Stuckey, Arron Afflalo, and Kevin Martin, for example), and certainly unable to be the best player on a good team.

And believe me, I realize that talking in abstract concepts like this can be silly. Despite history, which by the way only goes back ten years, a shooting guard’s blocks or steals per minute shouldn’t sway a team whether to take the guy or not. But having poor defensive stats all around – and I can do the same exercise with his poor defensive rebounding – does raise serious questions about Muhammad’s defense. Maybe someone with access to Synergy can shed more light here, but since Shabazz’s quickness and athleticism are questionable – and if you haven’t watched him play, believe me his quickness and athleticism are questionable (julienrodger from A Substitute for War has written a couple of good articles on the subject – look here and here), I’m not sure he wouldn’t be a defensive liability in the NBA.

So when you put it together you have a skilled scorer who is crafty though not particularly athletic, who couldn’t find the open man if he had five guys guarding him, and who has provided no evidence to suggest he’s even an average defender. This just doesn’t sound like a top five prospect or a game-changing star/primary option.

Of course, like with Ben McLemore, I’m not suggesting that you shouldn’t take Shabazz in the first round. I’d probably even take him in the lottery. He’s a good and versatile scorer. He hustles, and he steals a lot of boards on the offensive end. He obviously has a lot going for him, and I think he could be a decent to solid NBA player. Hell, O.J. Mayo is a decent to solid NBA player. But he never lived up to his superstar hype. And I’m not so sure Shabazz will either.

-James

Underrated Draft Prospects: Trey Burke

Burke certainly is an interesting prospect. Everyone and their mothers recognize him as the best point guard in college, he’s a sophomore by the way, and yet all of the big time draft sites peg him as a mid-first-rounder. So where’s the disconnect?

For one, Burke is pretty short. Now I’m not going to try to sell you the size doesn’t matter bullshit like I did last year, because size does matter, especially for wings and especially on defense. But size is less of a limitation for point guards than it is for other positions. And this is demonstrated quite convincingly by the size of some of the league’s best point guards. Chris Paul, of course, is one of the three best players in the league at six feet even with shoes on. And it doesn’t end there: Rajon Rondo, Mike Conley, Ty Lawson, and Kyle Lowry are elite at the position – and they’re all under 6’2″. Even Jameer Nelson, Raymond Felton, T.J. Ford, and Nate Robinson have had reasonable success in the NBA. And Burke has a case for being a better offensive college player than any of these guys. He has almost certainly been the best scorer of the bunch – shooting a 59% true shooting percentage while averaging more points per pace-adjusted 40 than all but Nelson (his senior year), who played against weaker competition. Plus Burke is on pace to average more assists per pace-adjusted 40 than every player on that list except T.J. Ford. Factor in turnover rate – Burke’s is the best of the bunch – and what we have is an efficient, finely tuned offensive weapon who is still only 20.

Though he is not a superb vertical athlete, Burke is extremely quick and fantastic at handling the ball. This allows him to create space and penetrate at a very high level, and because of his court vision and elite passing, he can find the open man when defenses collapse on him. It is difficult to find a comparison to Burke because of his offensive versatility. Chris Paul was not the scoring threat in college that Burke is, though he developed into a great scorer with time. Paul separates himself from Burke on the defensive end though, where his instincts were much better than Burke’s are. And this is where Burke’s critics are the harshest.

Burke steals the ball at a respectable rate, but his on-ball defense has been criticized as sub-par for an NBA prospect. However, while defense is unquestionably important, it is less of a factor for perimeter defenders than for interior defenders. I’ll expand more on this in a future post, but a bad defensive center is generally much more detrimental to a team than a bad defensive point guard. And I don’t think anyone is calling Burke a bad defender, only a sub-par one. Besides, quantifying defense by observation is tough and there is plenty of room for error. Either way, it is very doubtful that Burke’s shortcomings on the defensive end even approach canceling out his sensational offense.

My draft model, of course, projects Burke as a +2 in the league, which puts him in elite company, and suggests that he’s the fourth best prospect in the draft – and the second best point guard. As much as I love the top point guard prospect, Marcus Smart, his offense is just not on par with Burke’s at this point. As I’ve already noted, Burke’s quickness and ballhandling allows him to go just about anywhere on the court any time he wants. And this ability is amplified by his extraordinary jump shooting. Just a few weeks ago, Jonathan Givony tweeted that Burke was statistically the best off the dribble jump shooter in college basketball. Burke’s deadly shooting is the final piece in a combination that makes him a constant threat with the ball as soon as he crosses half court. And though his defense is pretty far behind his offense, it’s not far enough behind where I’d wait until the mid-first-round to take him. There are a very limited number of players in any given draft that will pan out in the NBA. Burke looks to be one of them – he crosses my +2 threshold and he’s one of the best players in college basketball as a sophomore. It would be a shame if he slipped past the top ten in this year’s draft.

-James